The Continuing Controversy Over DPAs and NPAs

There is a lot of grumbling these days over the Justice Department’s use of Deferred and Non-Prosecution Agreements. Some think the deals are too lenient and corporations should be required to plead guilty. Capitol Hill continues to question why individuals are not prosecuted in recent mega-settlements. Another area of criticism focuses on the detailed compliance conditions imposed on companies.

There is a lot of grumbling these days over the Justice Department’s use of Deferred and Non-Prosecution Agreements. Some think the deals are too lenient and corporations should be required to plead guilty. Capitol Hill continues to question why individuals are not prosecuted in recent mega-settlements. Another area of criticism focuses on the detailed compliance conditions imposed on companies.

One thing is clear – the use of DPAs and NPAs are increasing. In the early 2000s, there were less than five annually; now we see over 30 DPAs and NPAs a year. That is a significant increase and represents a real policy change by the Justice Department.

The Justice Department has become a lightning rod for public frustration over failure to prosecute any significant executives in the financial industry for the economic meltdown in 2008; failure to prosecute individuals in major AML/BSA sanctions settlements (e.g. ING Bank, HSBC); and “routine” use of NPA/DPAs in corporate settlements with detailed monitoring and compliance conditions.

Prosecution purists point to the pre-NPA/DPA era, when companies were either indicted or not indicted, with no in-betweens. The purists argue that companies should be required to please guilty to a criminal offense, agree to a fine, and detailed compliance conditions. Life was a lot easier then (in so many ways).

Prosecutors have a number of resolutions they can use. In some cases, they have had country or regional subsidiaries plead guilty and avoid making the parent company plead guilty.

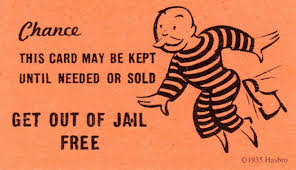

Prosecutors like to have a variety of tools. An up or down decision system – indict or decline to indict – does not give prosecutors any ability to address the hard cases, where they are more inclined to decline prosecution rather than indict.

Until the turn of the century, the old “up or down” system worked pretty well – companies were either indicted or not, and entered into criminal plea agreements. With the assistance of defense counsel, prosecutors started to embrace NPAs/DPAs as an alternative tool. From the company’s perspective, they avoided the impact of a criminal guilty plea. Prosecutors agreed to the new tool since they still secured a large fine and were able to impose proactive changes to improve corporate compliance programs.

In the context of FCPA cases, the Justice Department and the SEC have used corporate settlements to raise the bar for corporate compliance programs. In the last five years, the Justice Department and the SEC have incorporated new best practices and ideas from the compliance community in corporate settlements.

When corporate compliance failures result in FCPA violations, prosecutors have a responsibility to make sure that companies remediate those issues to prevent future violations. Unfortunately, FCPA settlements have turned into the Dead Sea scrolls and examined for “clues” as to the Justice Department/SEC’s latest thinking on compliance requirements. The FCPA Guidance, however, outlined a very specific set of requirements for compliance programs, but that has not stopped practitioners from engaging in the review and analysis of each FCPA settlement.

The debate will continue – I have no doubt of that. Nor should anyone expect the Justice Department or the SEC to stop using DPA/NPAs anytime soon. The debate is a healthy one and important for our criminal justice system and may have a long-term impact on prosecutors. For now, prosecutors continue to hold all the cards and corporations typically have a very weak hand to play.

The debate will continue – I have no doubt of that. Nor should anyone expect the Justice Department or the SEC to stop using DPA/NPAs anytime soon. The debate is a healthy one and important for our criminal justice system and may have a long-term impact on prosecutors. For now, prosecutors continue to hold all the cards and corporations typically have a very weak hand to play.

1 Response

[…] added to the FCPA. In the other corner stands Mike Volkov, who said in a recent post, entitled “The Continuing Controversy Over DPAs and NPAs”, that DPAs and NPAs are part of the growing arsenal of prosecutorial tools that can be brought […]