False Claims Act 2019 Year in Review

Jessica Sanderson, Of Counsel at The Volkov Law Group rejoins us for her annual review of False Claims Act enforcement. Jessica can be reached at [email protected].

2020 marks the 150th anniversary of the Department of Justice (“DOJ”), and it unwrapped a nice gift: On January 9, 2020, DOJ released its Fraud Statistics showing that it obtained more than $3 billion under the False Claims Act (“FCA”) for the federal government in Fiscal Year 2019. In this article, we simplify and display the DOJ statistics in graphs that reveal patterns and trends. We also highlight some of the significant FCA developments over the year. This article is not intended to be a comprehensive review of all FCA matters, so please contact the Volkov Law Group if you want to know more.

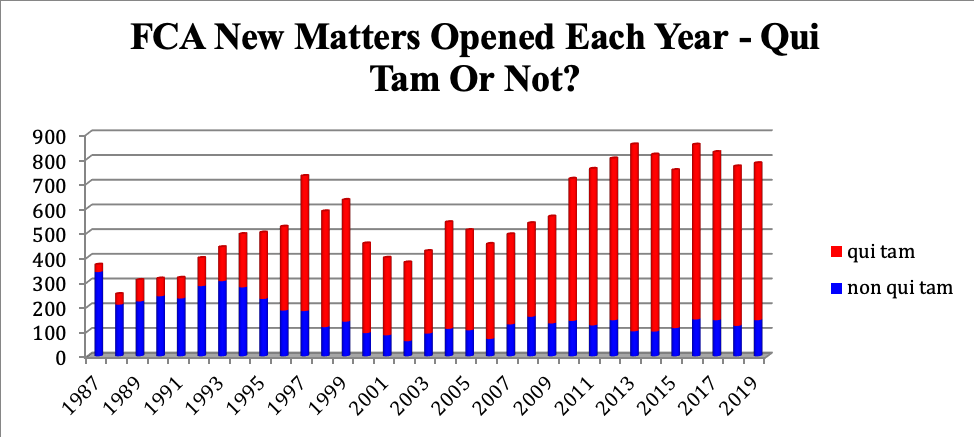

What do the statistics tell us? This was not a surprise party. The statistics show that the healthcare sector remains the top driver of FCA activity, as it has been both in terms of the number of new matters opened and the total dollars recovered for the past decade. The number of new matters opened, which had fallen for two years, ticked back up slightly in 2019. As usual, private individuals known as qui tam relators continued to initiate those new matters (relators instigated 84% of new matters in 2018 and 81% of new matters in 2019). But the numbers themselves don’t tell the whole story.

Sector Analysis

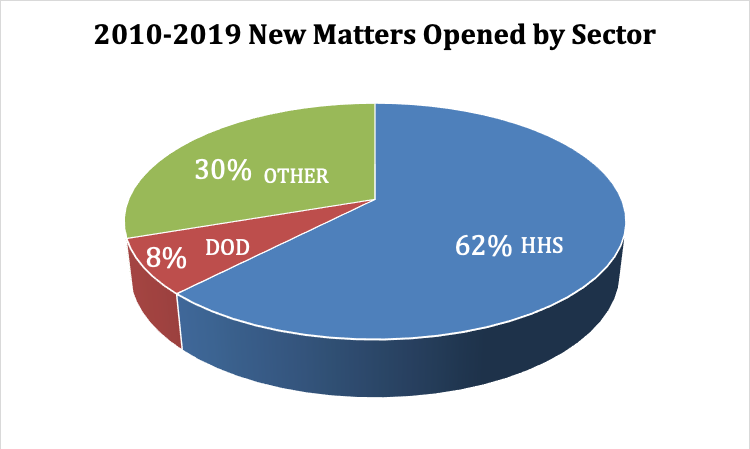

All individuals and companies that do business with the federal government must be mindful of the FCA. The government’s statistics, however, are divided into three categories only: Health and Human Service, Department of Defense and “Other.”

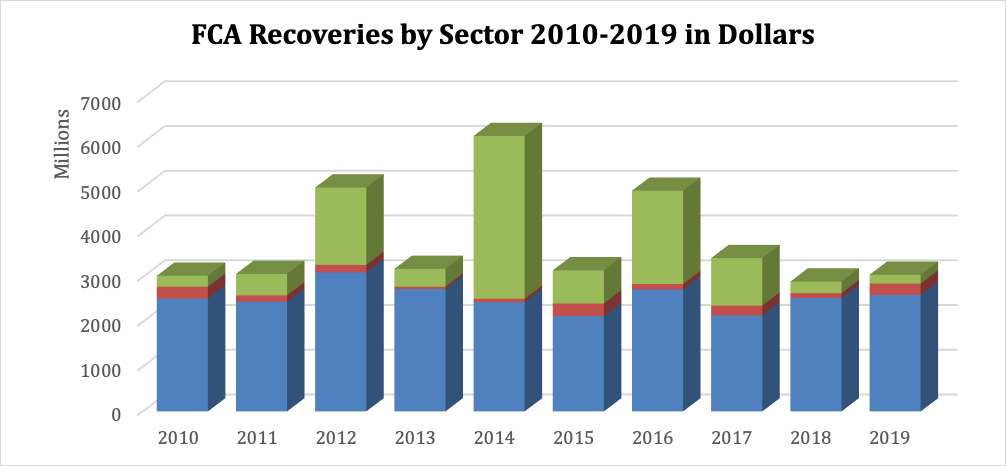

Recoveries: “Of the more than $3 billion in settlements and judgments recovered by the Department of Justice this past fiscal year, $2.6 billion relates to matters that involved the health care industry, including drug and medical device manufacturers, managed care providers, hospitals, pharmacies, hospice organizations, laboratories, and physicians.”[1] In July 2019, DOJ obtained $1.4 billion from Reckitt Benckiser Group plc alone related to marketing of the opioid addiction treatment drug Suboxone (the civil settlement with the federal government totaled $500 million). Total healthcare recoveries this year are consistent with prior years: Since 2010, DOJ’s civil healthcare fraud settlements and judgments have exceeded $2 billion annually.

Indeed, recoveries in both the healthcare and defense sector have been relatively constant over the last ten years. In 2018, DOD recoveries accounted for 4% of total annual recoveries. In 2019, DOD recoveries accounted for 8% of total annual recoveries. Looking at averages from 2010-2019, DOD recoveries accounted for 4% of total recoveries, with minor fluctuations.

In 2018, healthcare recoveries accounted for 87% of total annual recoveries. In 2019, healthcare recoveries accounted for 85% of the total. From 2010-2019, the amount of healthcare recoveries remained relatively consistent, but they only account for 67% of total recoveries over the period. The percentage is somewhat deceptive because the “other” category of recoveries has not been consistent.

In 2012, 2014, and 2016, total and “other” recoveries soared. The tremendous increase in “other” recoveries was predominantly attributable to settlements in connection with the 2008 mortgage crisis. In 2012, the government recovered $900 million from banks related to alleged mortgage fraud. In 2014, the government recovered $3.1 billion from banks and other financial institutions involved in making false claims for federally insured mortgages and loans. In 2016, recoveries in those cases totaled nearly $1.7 billion. Here’s what it all looks like:

New matters opened by sector have been remarkably constant over the last ten years.

Really, the only surprise in the “sector” statistics is the fact that DOD recoveries have not increased much over the last several years and have been so low in comparison to healthcare recoveries.

Consider this: In FY 2017, DOD spending accounted for 15.1% of the federal budget. In FY 2018, DOD spending accounted for 15.5% of the federal budget. And in FY 2019, DOD spending accounted for 15.7% of the federal budget. Indeed, DOD spent approximately $3 trillion over the last three years.[1] With consistently significant spending at the DOD, what explains the relatively fewer number of new matters opened and recoveries obtained in this sector, and when will we see the DOD numbers increase? Shouldn’t we be seeing at least double the amount of recoveries each year for DOD, closer to 15%?

Whistleblowers

Last year we predicted, “we fully expect individuals and the plaintiffs’ bar to continue push FCA enforcement in 2019 and into the foreseeable future.” No surprise, in 2019, whistleblowers accounted for more than $2.2 billion of the government’s total recoveries. Whistleblower claims comprised 72% of the government’s 2019 recoveries, compared to 74% of 2018 recoveries; and, as noted above, private individuals known as qui tam relators continued to initiate most new matters — relators instigated 84% of new matters in 2018 and 81% of new matters in 2019. The number of lawsuits filed under the qui tam provisions overall has grown significantly since 1986, with 636 qui tam suits filed this past year – an average of more than 12 new cases every week; almost twice a day! This means that relators are filing cases almost as often as most people brush their teeth!

Although whistleblowers initiate the vast majority of FCA cases, and recoveries in qui tam actions constitute the lion’s share of all recoveries, one thing is certain: The government recovers far more from qui tam cases in which it intervenes. In fact, recoveries in actions where the government does not intervene have never exceeded 17% of total annual recoveries (which was in 2017). As a practical matter, this means that one of, if not the most crucial stages in an FCA matter is the government’s determination whether to intervene.

Whistleblower Incentives: Under the FCA, whistleblowers may receive up to 30% of any recovery. Since 1987, whistleblowers have received approximately $7.5 billion in relator share awards. But relator share awards have been trending downward since 2016. In 2019, relators received approximately $272 million in awards. This figure is down significantly from 2018 and is the lowest number we have seen since 2009.

Although whistleblowers initiate far more FCA actions than the government, and whistleblowers’ actions account for largest portion of all settlements and judgments, the government also has been proactive in pursuing FCA violations. In 2019, the government opened 146 new matters (an average of nearly 3 cases a week).

What Happened at DOJ in 2019?

Guidance: In May 2019, DOJ released guidance regarding cooperation credit in FCA investigations.[1] The policy, incorporated in the Justice Manual at Section 4-4.112, identifies the type of cooperation eligible for credit. In announcing the policy, DOJ stated:

Under the policy, cooperation credit in False Claims Act cases may be earned by voluntarily disclosing misconduct unknown to the government, cooperating in an ongoing investigation, or undertaking remedial measures in response to a violation. Even if the government already has initiated an investigation, for example, a company may receive credit for making a voluntary self-disclosure of other misconduct outside the scope of the government’s existing investigation that is unknown to the government. Similarly, a company may earn credit by preserving relevant documents and information beyond existing business practices or legal requirements, identifying individuals who are aware of relevant information or conduct, and facilitating review and evaluation of data or information that requires access to special or proprietary technologies.

Notably, the Justice Manual at Section 4-4.112 (n.1) states that DOJ will also consider whether a corporate defendant had an effective compliance program at the time of the violation and/or decided to implement or improve its compliance program after an alleged violation, in evaluating a defendant’s civil liability under the FCA. DOJ referred to the criteria included in Justice Manual at § 9-28.800 regarding corporate criminal prosecutions, on “Corporate Compliance Programs.” The Volkov Law Group published earlier posts regarding the DOJ Guidance Document on “Evaluation of Corporate Compliance Programs,” updated in April 2019 (see, e.g. here). Once again, we cannot stress the importance of having an effective compliance program in potentially avoiding liability or reducing penalties.

On October 8, 2019, Assistant Attorney General for the Criminal Division Brian A. Benczkowski announced the issuance of new guidance that provides an analytical framework for evaluating assertions by a business organization that it cannot afford to pay a criminal fine or monetary penalty. Where legitimate questions exist regarding a company’s inability to pay, the government will consider a range of factors, including the company’s ability to raise capital and the significant and likely collateral consequences of the fine or penalty to the company.[2]

On October 28, 2019, U.S. Housing and Urban Development Secretary Ben Carson and U.S. Attorney General William Barr issued a Memorandum of Understanding (“MOU”) that provides guidance on the appropriate use of the FCA for violations by Federal Housing Administration (“FHA”) lenders.[3] The goal is to “not impede or discourage lenders from offering affordable FHA-insured loans to credit-worthy borrowers.” HUD expects that FHA requirements will be enforced primarily through HUD’s administrative proceedings. HUD will use the Mortgagee Review Board (“MRB”) to review and refer FCA claims. The MOU prescribes the standards for when HUD, through the MRB, may refer a matter to DOJ for pursuit of FCA claims, and also sets forth how DOJ and HUD will cooperate during the investigative, litigation, and settlement phases of FCA matters. The MOU also recognizes that the FCA requires, among things, a material violation of HUD requirements, and DOJ attorneys will solicit HUD’s views to determine whether the elements of the FCA can be established.

In December 2019, DOJ amended the civil fraud litigation portion of the Justice Manual (4-4.110, available here) to provide that in any FCA matter, the attorneys “will confer with the relevant agency during the investigative, litigation, and settlement phases of the matter.” US attorneys will “solicit the agency’s views on the” FCA claims, and, if, in a qui tam action, “the agency does not support the whistleblower’s pursuit of the matter, the agency may recommend that the [DOJ] seek dismissal of the case.”

DOJ Motions To Dismiss Qui Tam Cases: In last year’s FCA recap, we talked about the “Granston Memo” (incorporated in the Justice Manual at 4-4.111), which directs prosecutors to more seriously consider dismissing cases filed under the FCA’s qui tamprovisions when it furthers one or more policy goals.[4] By the end of FY 2019, Senator Grassley and others had serious concerns about DOJ’s, “implementation of the Granston Memorandum and its efforts to dismiss greater numbers of qui tam cases for reasons that appear primarily unrelated to the merits of individual cases.”[5] In a September 4, 2019 letter to Attorney General William Barr, Senator Chuck Grassley questioned the DOJ’s use of the Granston Memo, especially where dismissal was premised on an alleged waste of government resources in discovery and litigation. Grassley posited that such dismissals could discourage whistleblowers and “create perverse incentives for alleged fraudsters to engage in abusive litigation tactics to prompt a case’s dismissal.” Grassley provided several recent cases as examples.

In response, the DOJ explained that it had moved to dismiss only 45 out of 1,170 qui tam actions between January 1, 2018 and October 25, 2019.[6] The DOJ stated that those statistics (less than 4%) demonstrate that it has exercised its dismissal authority judiciously. While that may be true, the statistics also show that DOJ motions to dismiss are incredibly powerful.

The DOJ listed 42 of those 45 actions in which it sought dismissal (3 remain under seal and were not listed). Courts granted the DOJ’s motions to dismiss in 27 of the 28 cases with decisions.[7] That’s a 96% success rate. And of the entire 42 listed cases, only 4 currently remain pending at the trial or appellate level. Relators dismissed 9 cases and in one instance, the court granted the defendant’s motion to dismiss. Those statistics demonstrate that a qui tam relator has little chance of prevailing in the face of a government motion to dismiss (at best less than 10% based on these numbers). In fact, on November 14, 2019, during oral argument on an interlocutory appeal in the Ninth Circuit, in one of the two pending cases challenging a district court’s denial of DOJ’s motion to dismiss, the DOJ attorney stated, “there has never before been a district court order that refused to dismiss on the United States’ motion.”[8]

It’s also possible the Supreme Court will weigh in on this issue soon. In a qui tam case against JPMorgan, a district court granted the DOJ’s motion to dismiss the case, and the D.C. Circuit affirmed the ruling in August 2019. On November 20, 2019, the relator filed a petition for writ of certiorari to the Supreme Court asking it to resolve a circuit split as to “[w]hether the Government is entitled to absolute deference regarding its decision to dismiss an FCA action… .” [9]Responses to the petition are due on March 4, 2020.

2020 Focus? On November 5, 2019, the DOJ announced the formation of a new Procurement Collusion Strike Force (“PCSF”) focusing on schemes that undermine competition in government procurement, grant and program funding. Among other things, the PCSF set up a new online “Tip Center” where people can report suspected criminal activity affecting public procurement.[10] So maybe we will see the DOD and “other” categories start trending upwards.

What Happened in the Appellate Courts in 2019?

The Supreme Court weighed in on one FCA case in 2019. In a unanimous decision, the Supreme Court resolved a circuit split whether qui tam relators could take advantage of a statute of limitations tolling provision, under 31 U.S.C. §3731(b)(2), which provides that an action may be brought within three years of discovery (and within ten years of the last violation), in cases where the government has declined intervention.[11] The Supreme Court held, yes; the tolling provision applies regardless of whether the government intervenes and the relator in such a case would be considered “the official of the United States charged with responsibility to act in the circumstances.” As a result of this decision, providing relators with a longer time to file – perhaps up to four years longer – we expect to see additional cases surviving dismissal and larger recoveries (because of per claim penalties that would be applied to a larger number of claims).

Thefederal Courts of Appeal (and several district courts) grappled with a number of issues in the FCA space, which, given the number of new matters opened per year, is no surprise.

In the area of DOJ motions to dismiss (discussed above), a panel of the Ninth Circuit heard oral argument on November 14, 2019 in a case where the district court denied DOJ’s motion to dismiss. The panel hinted that DOJ “probably made a mistake” in seeking reversal of the district court’s denial of its motion to dismiss on interlocutory appeal, rather than trying to satisfy the district court’s concerns: “I mean, talking about diversion of government resources,” one judge commented.[12]

The First Circuit determined that the first-to-file bar is not jurisdictional, contributing to a circuit split. On January 13, 2020, the Supreme Court denied a petition for writ of certiorari in a case that might have resolved that split: The question presented was whether the first-to-file bar “is a jurisdictional provision that permits courts to consider all of the ‘facts underlying the pending action’ to determine its application.”[13]

In March 2019, in what “appear[ed] to be an issue of first impression,” the Fourth Circuit held that when the government declines to intervene in a qui tam action, the government “cannot be considered to have been a party to the FCA suit—with a full and fair opportunity to litigate the matter—for collateral estoppel purposes,” as it relates to a criminal proceeding based on the same misconduct.[14]

The Third and Fifth Circuits (and several district courts) dealt with the issue of materiality following the Supreme Court’s 2016 decision in Escobar.[15]

Lower courts grappled with pleading requirements and the application of Rule 9(b) in FCA cases. For example, in one case, the defendants argued that the relators did not see the actual Medicare bills and thus could not sufficiently allege the falsity of any claims for payment. The district court agreed, and the Eight Circuit affirmed. On November 25, 2019, the Supreme Court denied a writ of certiorari in the case, which might have provided clarity (question presented: were relators required to plead “the exact content of billings sent to Medicare – contents which were kept secret by management – in order to be able to survive a motion to dismiss made under Fed. R. Civ. P. 9(b)”).[16] The Supreme Court had earlier denied a petition also seeking clarification of Rule 9(b) requirements. There, the question presented was “[w]hether a court may create an exception to [Rule] 9(b)’s particularity requirement when the plaintiff claims that only the defendant possesses the information needed to satisfy that requirement.”[17]

All in all, it’s been

a very active year in the FCA realm. And we’re fairly certain 2020 will be

equally as dynamic. The Volkov Law Group will continue to monitor this area and

vlog about important FCA developments. As always, if you have any questions,

please feel free to contact any one of our attorneys.

[1] Press Release 19-478, “Department of Justice Issues Guidance on False Claims Act Matters and Updates Justice Manual” (May 7, 2019), available here.

[2] See “Assistant Attorney General Brian A. Benczkowski Delivers Remarks at the Global Investigations Review Live New York,” Oct. 8, 2019, available here and the Memo, available here.

[4] Memo, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Factors for Evaluating Dismissal Pursuant to 31 U.S.C. 3730(c)(2)(A) (Jan. 10, 2018), available at https://assets.documentcloud.org/documents/4358602/Memo-for-Evaluating-Dismissal-Pursuant-to-31-U-S.pdf.

[5] The September 4, 2019 letter is available here.

[6] The December 19, 2019 letter is available here.

[7] An additional case was dismissed in November 2019 but was not noted in the government’s list because it was generated as of October 25, 2019.

[8] Oral argument video available here.

[9] United States ex rel. Schneider v. JPMorgan Chase Bank N.A., No. 19-678, November 20, 2019 Petition for Writ of Certiorari available here.

[11] Cochise Consultancy, Inc., v. U.S. ex rel. Hunt, available here.

[12] United States v. United States ex rel. Thrower, No. 18-16408 (9th Cir.), November 14, 2019 oral argument video available here. A similar case is pending in the Seventh Circuit. United States ex rel. CIMZNHCA, LLC v. UCB, Inc., No. 19-2273 (appeal of district court denial of DOJ’s motion to dismiss). Oral argument is scheduled for January 23, 2020.

[13] Estate of Robert Cunningham v. McGuire, No. 19-583, October 25, 2019 petition, avaiable here

[14] United States v. Whyte, 918 F.3d 339 (4th Cir. 2019).

[15] The Volkov Law Group discussed Escobar on August 13, 2018, here. In Escobar, the Supreme Court ruled that the false certification theory of FCA liability required that a claim, “does not merely request payment, but also makes specific representation about the goods or services provided; and the defendant’s failure to disclose ‘material statutory, regulatory, or contractual requirements makes those representations misleading half-truths.’” In applying this standard, the Supreme Court directed lower courts to apply a “rigorous” and “demanding” materiality standard, suggesting that plaintiffs have to show that the government would have refused to pay if it knew of the alleged misrepresentations.

[16] United States ex rel. Strubbe v. Crawford County Memorial Hospital, No. 19-225 (cert. denied, Nov. 25, 2019), petition available here.

[17] Intermountain Health Care, Inc. v. United States ex rel. Polukoff, No. 18-911 (cert. denied, June 10, 2019), January 14, 2019 petition available here.