DOJ Indicts Former CEO of Cancer Treatment Company for Conspiracy

The Justice Department’s Antitrust Division’s criminal enforcement program is having a strong year. Since completing its long-term and record-setting prosecution of Japanese auto parts suppliers, the Antitrust Division focused attention on new industries, including generic pharmaceuticals, chicken processors, government contractors, electronic capacitors, and health care. It takes time to bring about results.

This year, the Antitrust Division, along with state prosecutors, focused on the Florida medical and radiation treatment industry in Florida. In April 2020, the Antitrust Division settled for $100 million with Florida Cancer Specialists & Research Institute (“FCS”) for a conspiracy to allocate cancer patients in Florida. FCS entered into a three-year deferred prosecution agreement. FCS conspired with competitors to allocate medical and radiation oncology treatments.

FCS also reached a settlement with Florida State prosecutors and agreed to pay $20 million to settle antitrust and false claims act claims.

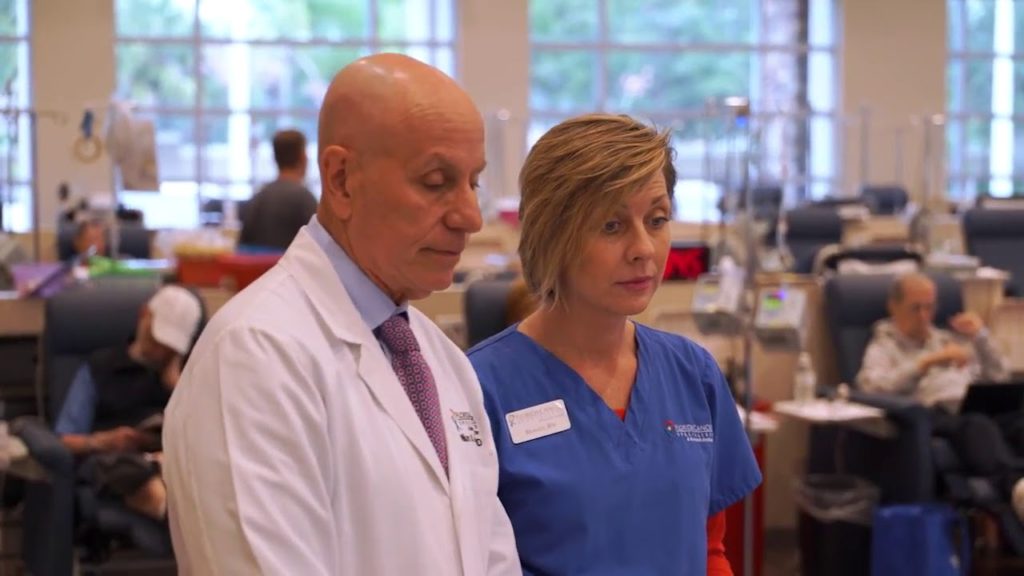

FCS is one of the largest hematology and oncology practices in Florida, which maintains around 100 offices and more than 200 doctors across the state.

Following the settlement with FCS, DOJ has indicted Dr. William Harwin, the founder and former President of FCS. Harwin is charged with conspiracy to allocate medical and radiation oncology treatments in Collier and Charlotte counties in Florida.

Starting in 1999 and continuing to 2016, Harwin and his co-conspirators entered into an illegal agreement to allocate medical oncology treatments for patients. Pursuant to the illegal agreement, FCS and the co-conspirators agreed that FCS would exclusively provide chemotherapy services to patients, and the competing oncology group would exclusively provide radiation oncology treatments to patients.

By dividing the market between themselves, FCS and the competing oncology group to operate with minimal competition thereby restricting choices and possible integrated care option for cancer patients.

The indictment cites specific examples when Harwin communicated with the competing oncology group referencing the illegal understanding between the two competitors.

For example, FCS and its competitor that FCS would not hire radiation oncologists and the competitor would not hire medical oncologists. On February 5, 2012, Harwin told an FCS colleagues that “there was no way I would be ok with [competitor] hiring med oncs, ours or others. Period.”

In another example, on February 21, 2012, after learning that the competitor co-conspirator was providing a chemotherapy treatment to cancer patients in violation of their illegal agreement, Harwin informed his counterpart at the competing co-conspirator that “we expect you will end this.”

In yet another example, on April 15, 2013, after the competitor co-conspirator acquired a medical oncology group that employed oncologists, Harwin told his counterpart to “make [them] disappear.”