False Claims Act 2020 Year in Review: The FCA “Has Never Been More Important Than it is Right Now”

Jessica Sanderson, Partner at The Volkov Law Group, joins us for her annual False Claims Act Review. Jessica can be reached at [email protected].

$1.9 trillion dollars of federal spending on the horizon. That’s right, immediately following his inauguration in 2021, President Biden proposed a $1.9 trillion stimulus plan to help recover from the COVID-19 pandemic. This follows the approximately $3.5 trillion of federal government funds authorized under various COVID-19 relief packages passed in March and April 2020, and the $920 billion stimulus package passed on December 27, 2020. In total, the U.S. government spent $6.5 trillion in fiscal year (“FY”) 2020 (October 1, 2019 through September 30, 2020), $6,551,872,000,000.00 to be more precise, which was a $2 trillion increase – up 47% – from FY 2019.

This article will review significant developments in the civil False Claims Act (“FCA”) area from the past year, but it’s hard to resist starting with predictions for FY 2021 and the near future. With such mind-boggling federal spending in FY 2020 and the obvious potential for fraud, abuse, and misuse of the trillions of dollars of federal stimulus funds, we undoubtedly will see a considerable increase in FCA audits, investigations, enforcement actions, qui tam lawsuits, settlements and judgments over the next 2-3 years. As Senator Grassley said in remarks delivered on the Senate floor on Whistleblower Appreciation Day (July 30, 2020), the FCA “has never been more important than it is right now” (Grassley also called whistleblowers “patriots”).

And now, let’s look at FY 2020. On Thursday, January 14, 2021, while Acting Attorney General Jeffrey A. Rosen was attending a briefing at the FBI’s Strategic Information and Operations Center to discuss security for the upcoming presidential inauguration following the recent capitol attack, the Department of Justice (“DOJ”) released its Fraud Statistics for the Fiscal Year 2020. “Even in the face of a nationwide pandemic,” DOJ announced, it “obtained more than $2.2 billion in settlements and judgments from civil cases involving fraud and false claims against the government.”

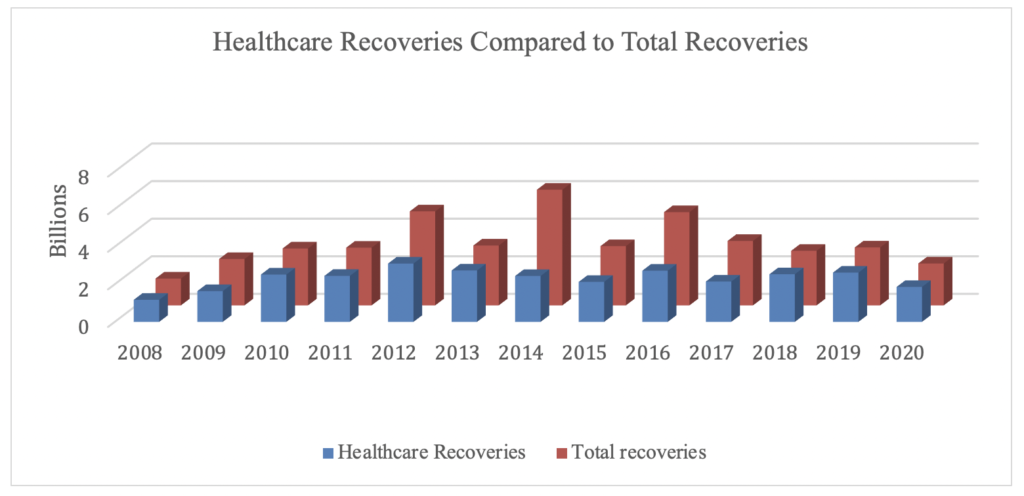

$2.2 billion sounds like a lot, but FY 2020 recoveries are down nearly $800 million from last year’s recoveries. In fact, it is the lowest total FCA annual recoveries since FY 2008. And approximately one quarter of those total recoveries came from a resolution with one company (in July 2020, Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation agreed to pay more than $642 million).

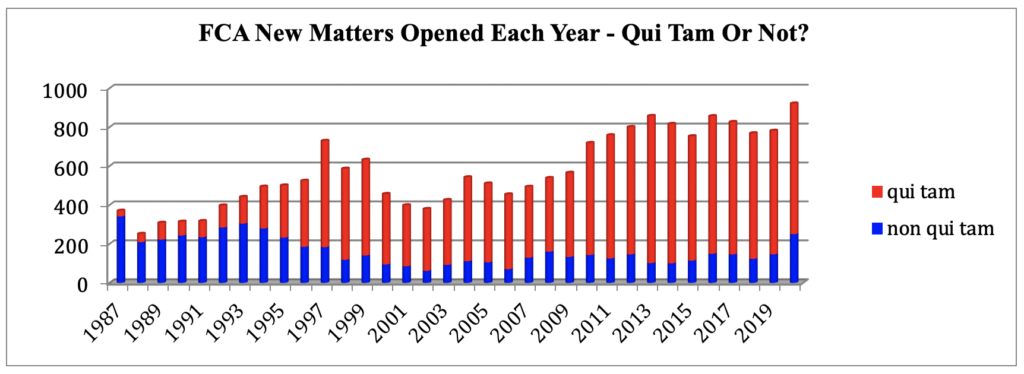

The statistic we find most remarkable this year is the 250 non-qui tam new matters that the government opened in FY 2020. This number is a significant increase over the 148 non-qui tam new matters opened in FY 2019, and is, in fact, the largest number of non-qui tam new matters opened in any single year since FY 1994, and the fifth (5th) largest number of non-qui tam new matters opened in any single year since FY 1987, shortly after Congress increased whistleblower incentives and DOJ began tracking these figures.

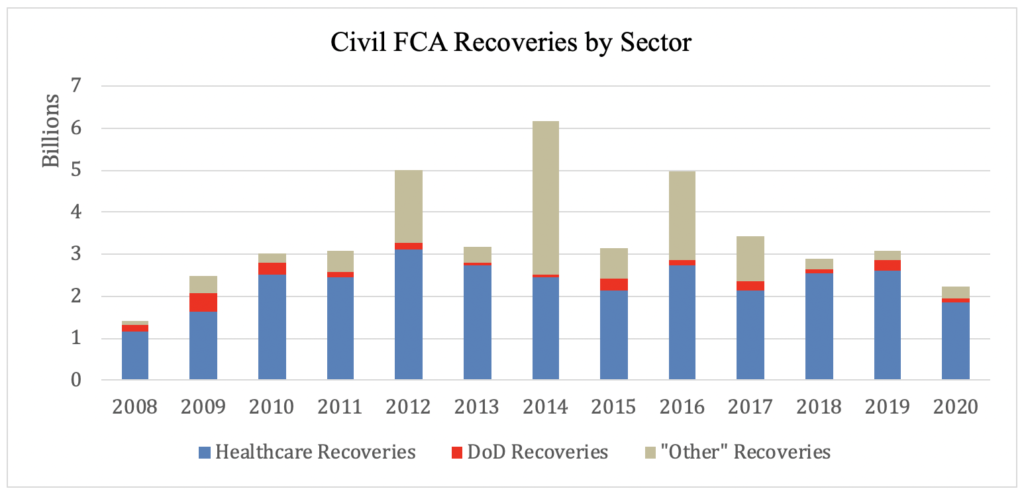

Digging into these numbers, we learn that in FY 2020, the government initiated more than twice as many healthcare fraud related matters (117 v. 57) and more than twice as many DoD/procurement fraud related matters (29 v. 13) than it did in FY 2019, and this was during the pandemic. That’s impressive: this means that on average the government was responsible for opening one new FCA matter on every single business day of the past year. Here’s what the trend looks like:

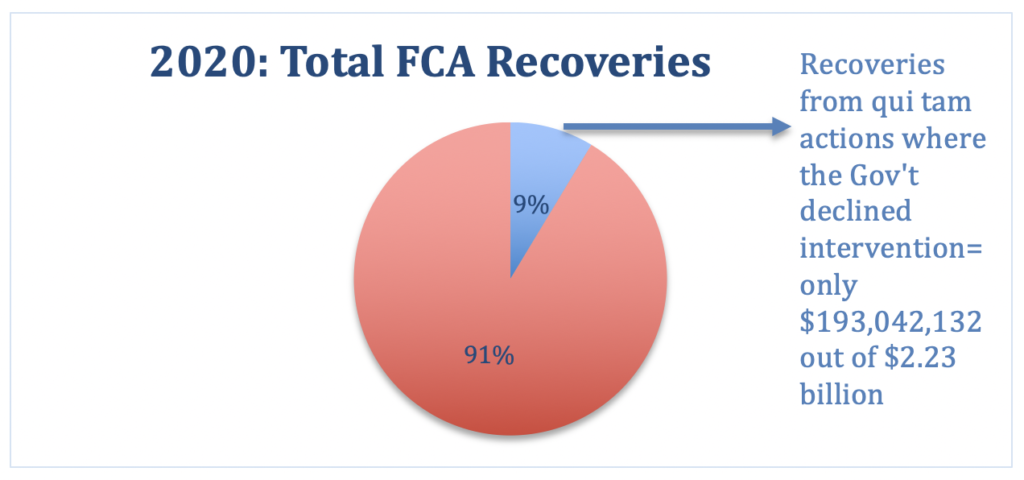

Considering the additional fact that the government tends to initiate and/or intervene in matters that have a far greater chance of ultimately obtaining significant recoveries (e.g., in FY 2020, less than 9% of total recoveries were obtained from qui tam cases where the government declined intervention) we should see record-breaking recoveries in the next few years when all of the new matters are resolved.

In fact, FY 2021 is already on track to be a record-breaking year because the FY 2020 statistics do not include DOJ’s resolution with Purdue Pharma LP and its owners in which Purdue agreed to pay $2.8 billion and the owners agreed to pay $225 million to resolve alleged civil FCA violations related to kickbacks and false marketing of opioids. The settlement was announced in October 2020, and a federal bankruptcy court approved the resolution in November 2020. In addition, in July 2020, Indivior Solutions agreed to pay $300 million to resolve civil FCA allegations related to its promotion of an opioid addiction treatment drug. That resolution is not credited towards FY 2020 because the court did not accept the company’s related criminal plea until November 2020. If those two resolutions alone are credited to FY 2021, total recoveries will exceed $3.325 billion, which already exceeds the federal government’s total annual recoveries in each of the fiscal years 2018, 2019 and 2020.

Sector Analysis

All individuals and companies that do business with the federal government must be mindful of the FCA. The government’s statistics, however, are divided into three categories only: Health and Human Service, Department of Defense and “Other.”

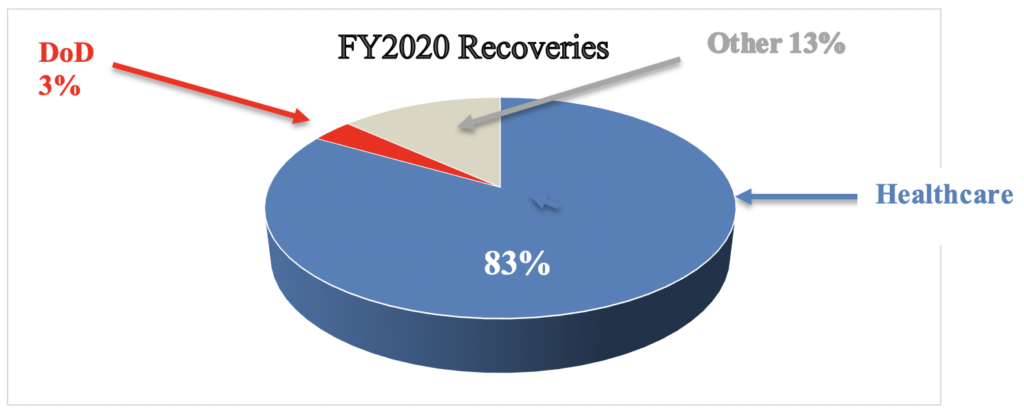

Healthcare: In releasing the statistics, DOJ announced,“Of the more than $2.2 billion in settlements and judgments recovered by the Department of Justice this past fiscal year, over $1.8 billion relates to matters that involved the health care industry, including drug and medical device manufacturers, managed care providers, hospitals, pharmacies, hospice organizations, laboratories, and physicians.” Total healthcare recoveries this year are consistent with prior years in terms of the total percentage of FCA recoveries. In FY 2020, healthcare recoveries accounted for 83% of the total FCA recoveries; in FY 2019, healthcare recoveries accounted for 85% of the total FCA recoveries. However, this is the first year since FY 2009 that DOJ’s civil healthcare fraud settlements and judgments have not exceeded $2 billion annually. Here’s what that looks like:

In FY 2020, DOD recoveries accounted for 3.4% of total annual recoveries; in FY 2019, DOD recoveries accounted for 8% of total annual recoveries, which was unusually high. Looking at averages from 2010-2020, DOD recoveries typically account for only 4% of total recoveries, with minor fluctuations.

We are still surprised that DOD recoveries have not increased much over the last several years and have been especially low in comparison to healthcare recoveries. Consider this: In FY 2020, DOD spending totaled $690 billion (not including other military-related spending, such as Homeland Security and Veterans Affairs spending), which accounted for approximately 11.5% of total major agency spending. HHS spending accounted for 22.3% of major agency spending that year. In 2019, DOD and HHS spending accounted for 16.6% and 26.1%, respectively, of the federal budget, and in FY 2018, DOD and HHS spending accounted for 16.5% and 25.4%, respectively, of the federal budget. With consistently significant spending at the DOD in the range of 15% annually, not that far below the percent of HHS spending, what explains the relatively smaller recoveries obtained in this sector, and when will we see the DOD numbers increase? Instead of 4%, shouldn’t we be seeing at least double the amount of recoveries each year for DOD, closer to 10-15%? Now that lawmakers like Grassley are calling whistleblowers “patriots,” perhaps we will see more qui tam activity in the DOD space.

Whistleblowers

As always, whistleblowers continue to drive FCA matters and recoveries. Qui tam relators opened 672 new matters this year, which averages out to nearly 13 cases each week. Add this to the DOJ’s 250 new matters in FY 2020 and the 1,558 total new matters opened in 2018 and 2019 (and the recent surge in federal spending), and you can see why we predict massive FCA recoveries over the next few years.

Relators were responsible for $1,686,124,824 in recoveries in FY 2020 (nearly 76% of total recoveries), which is a slight increase from FY 2019 (whistleblower claims comprised only 72% of the government’s recoveries).

Relator share awards in FY 2020 were down from FY 2019 in terms of actual dollars awarded ($309,416,126 compared to $365,623,744), but relator share awards actually increased slightly relative to total actual recoveries (13.9% of total recoveries, up from 11.8%). Since 1987, whistleblowers have received more than $7.8 billion in relator share awards.

As in prior years, although whistleblowers initiate the vast majority of FCA cases, and recoveries in qui tam actions constitute the lion’s share of all recoveries, one thing remains constant: The government recovers far more from qui tam cases in which it intervenes. In FY 2020, recoveries in qui tam actions where the government declined intervention constituted only 8.6% of total recoveries. As a practical matter, this means that one of, if not the most crucial stages in an FCA matter is the government’s determination whether to intervene.

What Happened at DOJ in FY 2020

Penalties: In June 2020, DOJ raised the per claim penalties under the FCA to $11,665 – $23,331 per violation occurring after Nov. 2, 2015 and assessed after June 19, 2020 (when the new penalties were adopted and published in the Federal Register).

Guidance: Also in June 2020, DOJ updated its “Evaluation of Corporate Compliance Programs.” Although the guidance document was issued by the DOJ criminal division, it is important to consider in the civil FCA context as well. The Justice Manual at Section 4-4.112 (n.1) states that DOJ will consider whether a corporate defendant had an effective compliance program at the time of the violation and/or decided to implement or improve its compliance program after an alleged violation when evaluating a defendant’s civil liability under the FCA. That section further refers to the criteria included in the Justice Manual at Section 9-28.800 regarding corporate criminal prosecutions, on “Corporate Compliance Programs.” The Volkov Law Group has published earlier posts regarding the June 2020 DOJ guidance document, so we will not cover it in detail in this article (see, e.g. here). Once again, however, we cannot stress enough the value of having an effective compliance program to potentially prevent or detect corporate misconduct, be it civil or criminal in nature. It may also contribute to charging decisions, reduced penalties, and the decision whether to impose a corporate integrity agreement (“CIA”). HHS OIG, for example, negotiates CIAs with health care providers and other entities as part of many FCA settlements, and those entities agree to the obligations in exchange for OIG not seeking their exclusion from participation in federal health care programs. “CIAs have many common elements, but each one addresses the specific facts at issue and often attempts to accommodate and recognize many of the elements of preexisting voluntary compliance programs.”) See HHS OIG website (emphasis added).

DOJ Motions To Dismiss Qui Tam Cases: In last year’s FCA recap, we talked about the “Granston Memo,” which directs prosecutors to more seriously consider dismissing cases filed under the FCA’s qui tam provisions when it furthers one or more policy goals. Since that time, there has been an uptick in the government’s exercise of its right to dismiss qui tam cases (“[d]uring the thirty years before the Granston Memo, the government moved to dismiss roughly 45 qui tam cases; in the two-plus years following the memo, [DOJ] moved to dismiss around 50 qui tams”). Thus, in 2020 the federal courts continued to grapple with the standard of review for such dismissals (discussed below). In fact, lawmakers like Senator Grassley are considering FCA amendments to restrict DOJ’s ability to dismiss qui tam cases. In Grassley’s speech quoted at the outset of this article, for example, he discussed his proposed “Whistleblower Programs Improvement Act,” and emphasized, “it’s especially ironic that the Department of Justice has been continuing its recent practice of dismissing charges in many of the False Claims Act cases brought by whistleblowers without stating its reasons. This is not the right approach. If there are serious allegations of fraud against the government, the Attorney General should have to state the legitimate reasons for deciding not to pursue them in court. …My legislation clarifies ambiguities created by the courts and reigns in this practice … .”).

What Happened in the Courts in 2020?

The U.S. Supreme Court did not rule on any FCA cases in 2020. But the Court did deny petitions for writ of certiorari challenging a few significant appellate court decisions.

In United States ex rel. Integra Med Analytics LLC v. Baylor Scott & White Health, 816 F. App’x 892 (5th Cir. 2020), for example, the Fifth Circuit affirmed the lower court’s dismissal of a case alleging fraudulent upcoding of Medicare claims. The claims against the Medicare provider were largely based on statistical data derived from publicly available information. In December 2020, the Supreme Court denied the whistleblower’s petition for review. Although the denial means that it will now be more difficult for ‘professional whistleblowers’ to comb publicly available data and bring cases in the Fifth Circuit based on statistical evidence, other circuits are more lenient.

In April 2020, the Supreme Court denied a petition for certiorari in U.S., ex rel. Schneider v. JPMorgan Chase Bank, N.A. (No. 19-678), which would have provided guidance on the standard of dismissal when the government moves to dismiss a qui tam case. The issue presented was whether the government is entitled to unfettered discretion or whether a qui tam relator should be able to demonstrate that the government’s rationale for dismissal was “fraudulent, illegal, or arbitrary and capricious.” As discussed further below, there is a circuit split regarding the standard of review of the government’s right to seek dismissal.

On September 16, 2020, the defendant filed a petition for writ of certiorari seeking review of the Third Circuit’s decision in United States ex rel. Druding v. Care Alternatives (discussed immediately below).

The Circuit Courts and Matters of First Impression: Virtually every clause of the FCA has been litigated excessively. Thus, we were surprised this year to see how many times the federal appellate courts considered matters of first impression.

In United States ex rel. Druding et al. v. Care Alternatives, 952 F.3d 89 (3rd Cir. 2020), for example, in a “matter of first impression” for the Third Circuit, the court held that for purposes of FCA “falsity,” a claim need not be “objectively false.” Instead, under a theory of “legal falsity,” a claim may be “false” if it fails to comply with statutory and regulatory requirements. In addition, “medical opinions may be ‘false’ and an expert’s testimony challenging a physician’s medical opinion can be appropriate evidence for the jury to consider on the question of falsity,” i.e., an expert opinion may be sufficient to create a genuine issue of material fact sufficient to avoid summary judgment. As a practical matter, this means that a medical provider’s judgment or opinion may be actionable as a “false” claim whenever the government or qui tam plaintiff can find an expert to contradict the opinion. The defendant filed a petition for certiorari asking the Supreme Court to weigh in on the matter, and we will continue to monitor developments.

Notably, the Ninth Circuit grappled with a similar issue in United States ex rel. Winter v. Gardens Regional Hospital et al., 953 F.3d 1108 (9th Cir. 2020). In that case, the court held “that the FCA does not require a plaintiff to plead an ‘objective falsehood.’ A physician’s certification that inpatient hospitalization was ‘medically necessary’ can be false or fraudulent for the same reasons any opinion can be false or fraudulent.” Because “medical necessity” is a condition of payment, every Medicare claim includes an express or implied certification that treatment was medically necessary. Claims for unnecessary treatment, therefore, may be false claims.

Ruckh v. Salus Rehabilitation, LLC, 963 F.3d 1089 (11th Cir. 2020), in relevant part, began “by noting that this Court has not previously addressed the appropriate standard to prove causation in FCA ‘cause to be presented’ actions.” The defendants at issue were management service providers that did not directly submit claims for payment for services to the government. Instead, the entities provided and pressured employees to use certain codes (“RUG codes”) that would cause Medicare to pay higher rates to the skilled nursing facilities (“SNFs”) that the entities served. The court looked to the “proximate causation” standard to determine whether there was a sufficient nexus between the defendants’ conduct and the submission of a false claim and held that there was. “At its core, the concept of upcoding is a simple and direct theory of fraud. SNFs receive money from Medicare based on the services they provide. In this case, the SNFs indicated they had provided more services—in quantity and quality—than they, in fact, provided. Therefore, Medicare paid the SNFs higher amounts than they were truly owed.” Because (1) the management companies’ conduct was “a substantial factor in inducing providers to submit claims for reimbursement,” and (2) “the submission of claims for reimbursement was reasonably foreseeable or anticipated as a natural consequence of defendants’ conduct,” the management companies may have “caused” the submission of false claims.

Notably, in U.S. ex rel. Benaissa v. Trinity Health, 963 F.3d 733 (8th Cir. 2020), the Eight Circuit made clear that a relator still must identify at least one, actual representative false claim submitted to federal healthcare programs or otherwise plead specific facts supporting a strong inference that claims were actually submitted in order to meet Rule 9(b) pleading requirements. Relators cannot simply claim that all or some percentage of claims must have been submitted.

As noted above, DOJ’s increased use of motions to dismiss qui tam actions has caused the courts to grapple with the standards for dismissal. There is a circuit split centered on whether the government has an absolute or “unfettered” right to dismiss or whether the government must demonstrate more. In United States ex rel. Borzilleri v. AbbVie, Inc., 2020 WL 7039048 (2d Cir. 2020) (a summary order that does not have precedential effect) the Second Circuit affirmed the district court’s order granting DOJ’s motion to dismiss a qui tam case in which it did not intervene. The Second Circuit, after acknowledging that it had not previously determined the standard of review ultimately did “not decide which standard should govern,” because it held that the relator failed to meet even the more stringent standard adopted by the Ninth Circuit in United States ex rel. Sequoia Orange Co. v. Baird- Neece Packing Corp., 151 F.3d 1139, 1145 (9th Cir. 1998)

In United States ex rel. Thrower v. Academy Mortgage Corp., 968 F.3d 996 (9th Cir. 2020), the Ninth Circuit was “presented with a question of first impression in the federal courts: is a district court order denying a Government motion to dismiss an FCA case under § 3730(c)(2)(A) an immediately appealable collateral order?” The Ninth Circuit held it is not; the court dismissed the government’s appeal for lack of jurisdiction because the district court’s order was not an immediately appealable collateral order. The court suggested in a footnote, however, that it may have ruled otherwise had the government first intervened. This decision not only forces the government (the victim) to expend resources litigating a case that it determined is not in its best interests to pursue, but also effectively makes the district court’s order unreviewable: If the qui tam plaintiff prevails, the government likely will not appeal the order and again seek dismissal when it stands to gain the lion’s share of the recovery, and a court is unlikely to reverse a decision denying a motion to dismiss after the qui tam plaintiff prevailed on the merits. If on the other hand the qui tam plaintiff ultimately loses the case, by that time the government will already have incurred the litigation burden and expense that it sought to avoid when it moved for dismissal in the first instance and likely will not wish to expend even further resources appealing a decision that is essentially moot.

Notably, in United States ex rel Cimznhca, LLC v. UCB, Inc., 970 F.3d 835 (7th Cir. 2020) the Seventh Circuit resolved a similar issue by holding that under the circumstances, the district court should treat DOJ’s a motion to dismiss a qui tam complaint in which it had not intervened as both a motion to intervene and to dismiss. Based on the holdings of Thrower and Cimznhca, we expect that DOJ will now as a matter of course simultaneously move to intervene in qui tam cases that it seeks to dismiss.

In Lestage v. Coloplast Corp., 982 F.3d 37 (1st Cir. 2020), the First Circuit decided a case that “raise[d] an issue of first impression” as to the proper causation standard for a retaliation claim under 31 U.S.C. § 3730(h). The FCA forbids employers from discriminating against an employee “because of” his or her protected conduct, and the parties in that case disputed the proper meaning of “because of.” The First Circuit joined the Third, Fourth, Fifth, and Eleventh Circuits in holding that the “but-for” causation standard applies (as opposed to a “motivating factor” standard).

Conclusion: Predictions for FY 2020 and Beyond

DOJ: First a word about the leadership: Years before he assumed the post, former-Attorney General William Barr viewed the FCA qui tam provisions as “basically a bounty hunter statute . . . an abomination . . . [he] wanted to attack.” By contrast, based publicly available information, it seems that President Biden’s pick for Attorney General, Judge Merrick Garland, has a more favorable view of the FCA. In Judge Garland’s May 9, 2016 Questionnaire for Judicial Nominees (submitted when he was under consideration for the Supreme Court), he identified two of his FCA opinions: U.S. ex rel. Yesudian v. Howard Univ., 153 F.3d 731 (D.C. Cir. 1998) (a whistleblower retaliation case) and a dissenting opinion inU.S. ex rel. Totten v. Bombadier Corp., 380 F.3d 488 (D.C. Cir. 2004). We’ve not located any others. In both of those decisions, Judge Garland seemed to take a more expansive view of the FCA than his colleagues on the bench.

In Totten, Judge Roberts (before appointment to the Supreme Court) wrote the majority opinion holding that an invoice submitted to Amtrak for payment was not actionable as a claim presented to the government. The panel held that the government may not recover against a contractor that presents a false claim to a federal grantee unless the grantee presents that false claim to the government. Judge Garland dissented, arguing that the alleged conduct violated the FCA as a false statement made “to get” the government to pay a false claim. Judge Garland wrote, “Although Amtrak receives billions of dollars in federal funds that it uses to pay contractor invoices, because it does not (and is not required to) re-present those invoices to the federal government, the court’s ruling immunizes those who defraud even that government-funded corporation from False Claims Act liability.” A unanimous Supreme Court later agreed with Judge Garland’s dissent in Allison Engine Co. v. United States ex rel. Sanders, 553 U.S. 662 (2008), holding that a plaintiff need not show that a defendant’s false record or statement was submitted directly to the government; submission to a government contractor or grantee is sufficient.

In Yesudian, regarding the standards for a whistleblower retaliation claim, the district court concluded there was no evidence from which a jury could reasonably have found that the plaintiff had engaged in protected conduct because “he never initiated a government investigation or a private qui tam suit.” The district court also held there was no evidence to demonstrate that the defendant knew the plaintiff was engaged in protected activity because he “never suggested to defendant that he intended to utilize his allegations in furtherance of” an FCA action. Judge Garland disagreed and wrote the opinion holding that an investigation of misconduct may constitute protected activity and that all the defendant need know is that the plaintiff was engaging in that protected activity. The FCA does not require an actual or threatened FCA government investigation or lawsuit. In fact, the plaintiff and defendant “need not know, or be advised, that [the conduct under investigation] would violate” the FCA. The decision also hints that Judge Garland will take an expansive view of the “presentment” requirement of a substantive FCA claim (“As [plaintiff] suggests, it is also possible to read the language to cover claims presented to grantees, but ‘effectively’ presented to the United States because the payment comes out of funds the federal government gave the grantee”).

As a prosecutor, Judge Garland primarily worked on criminal matters. Thus, while he undoubtedly had exposure to FCA investigations and prosecutions, his tenure as a prosecutor does not provide much insight as to his views of the FCA.

Now a Word about DOJ’s Current and Future Focus, we are back to where we started with predictions for the near future – “follow the money!” Fortunately, in June 2020, the Principal Deputy Assistant Attorney General for DOJ’s civil division, Ethan P. Davis, gave a speech that provides further valuable insights and confirms our predictions. Even with his departure from DOJ and the change in Administration, we expect DOJ’s enforcement priorities to hold true.

First, we expect to see the FCA used as a forceful “weapon” to “prevent wrongdoers from exploiting the COVID-19 crisis.” Davis noted, for example, that borrowers under the Paycheck Protection Program (“PPP”) must certify that “current economic uncertainty” makes the “loan request necessary to support the ongoing operations of the” borrower. The borrower also must promise to use the funds solely “to retain workers and maintain payroll or make mortgage interest payments, lease payments, and utility payments.” Finally, to seek forgiveness of the loan, the borrower must “certify that the funds were in fact used to pay costs that are eligible for forgiveness.” If any of these certifications are false, that could be actionable under the FCA. Davis also noted that the DOJ’s Civil Fraud Section has implemented a number of initiatives to identify, monitor, and investigate potential violations of the FCA related to the PPP and is working closely in this regard with the OIG of the Small Business Administration. We expect those initiatives to bear fruit.

Similarly, the CARES Act authorizes loans to small and medium-sized businesses, and borrowers and lenders are required to abide by the programs’ requirements. DOJ will use the FCA to recover from any parties that fail to comply or falsely certify compliance with CARES Act requirements. And private equity firms that invest in companies receiving CARES Act funds also should avoid taking any active role in any fraudulent conduct by the acquired company: Davis noted, “[w]here a private equity firm knowingly engages in fraud related to the CARES Act, [DOJ] will hold it accountable.” DOJ will also use the FCA to recover from any healthcare providers who receive stimulus funds that do not meet eligibility requirements or otherwise make false claims for such funds.

Second, the opioid crisis should continue to be a major priority for DOJ. Companies at all levels of the distribution chain, including pharmaceutical companies, drug wholesalers, pharmacies, and doctors may be targets of investigation and/or litigation. The large FCA resolutions with Purdue Pharma, Insys, Indivior, and Reckitt Benckiser may just be the tip of the iceberg.

Third, Davis added, he expects to see increased enforcement relating to “nursing homes and fraud on the elderly,” in particular where nursing homes provide substandard care to their residents. Davis also indicated, “Medicare Part C is an area where you can expect to see enforcement efforts in the years to come.”

That’s all for now. This article is not intended to be a comprehensive review of all FCA matters, so please contact The Volkov Law Group if you want to know more.