British American Tobacco’s Financial Scheme to Avoid Sanctions Detection (Part II of II)

British American Tobacco’s deceit and elevation of business over compliance permeates its recent blockbuster settlement for $629 million with the Department of Justice and Office of Foreign Asset Control. Importantly, the BAT settlement confirms DOJ’s new, aggressive approach to sanctions and export enforcement, and OFAC’s imposition of a penalty equal to the statutory maximum.

For compliance professionals, the BAT scheme is interesting to review because of its elaborate use of front companies and attempts to disguise North Korean connections. BAT partnered with North Korea to establish and operate a cigarette manufacturing business and relied on a network of financial facilitators linked to North Korea’s WMD proliferation network.

In 2001, BAT’s Singapore subsidiary, British-American Tobacco marketing (Singapore) (“BATM”) and a North Korean company, North Korea Tobacco Company (“NKTC”) formed a joint venture in North Korea to manufacture and sell cigarettes. BATM held a 60 percent stake in the joint venture and provided supplies, equipment, tobacco and other material (“Kit Sets”) needed to manufacture and sell cigarettes.

In 2007, BAT’s senior executives approved a scheme whereby BAT’s subsidiary would sell its stake in the joint venture to a Singapore-based trading group (“company 1”) for one euro due to its concerns over its public association with North Korea and difficulty extracting profits from North Korea. The divestment purposefully obscured BAT’s continued control and ownership over the joint venture. Indeed, company 1 understood it would act “as a vehicle for BAT to bring out [the joint venture’s] money and distribute back to BAT.” BAT continued to exercise control over the joint venture through restrictions in the sales agreement, including the right to reacquire its stake in the joint venture for a payment of one euro. BATM continued to receive payment for Kit Sets and other goods and services provided to the joint venture.

Senior managers at BAT understood that BAT continued to control the joint venture, and the substitution of the new company, the 50 percent JV owner, was only designed to ensure that BAT could extract funds from North Korea business operations. BAT create a false appearance that it no longer conducted business in North Korea.

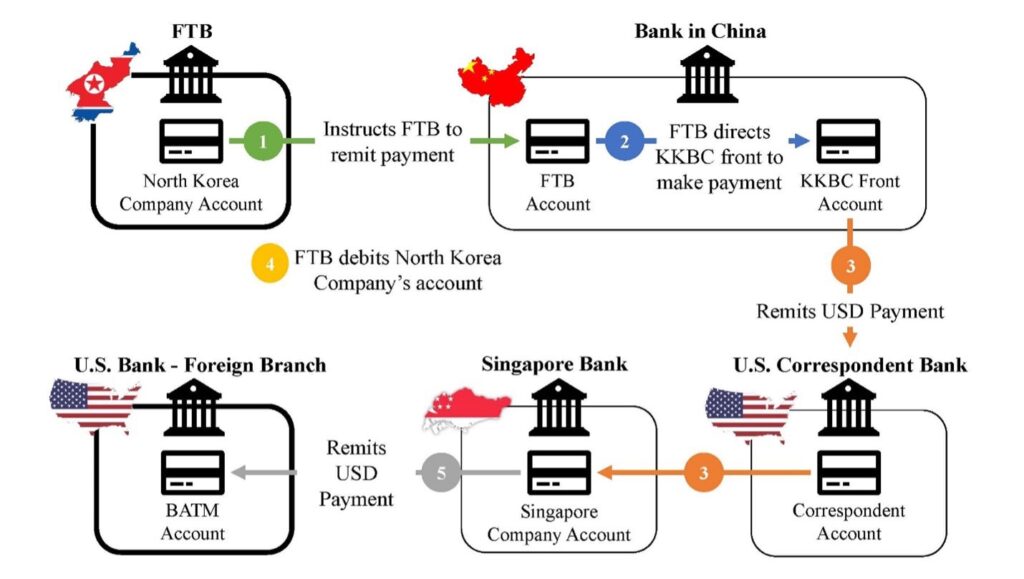

Between 2009 and 2016, the North Korean company remitted joint venture profits, including payments to BAT’s Singapore subsidiary, through a complex system that involved both OFAC-sanctioned Foreign Trade Bank (“FTB”) and Korea Kwangson Banking Corporation (“KKBC”).

BAT’s scheme was fairly straightforward, when mapped on paper, and involved several critical steps to disguise the source of revenues.

- A BAT subsidiary (“BATMS”) shipped goods, primarily cigarette components, to the joint venture (“JV”), in care of the front company (“company 1”);

- BATM invoiced company 1 for the goods;

- Company 1 sent the invoice to an employee at the North Korean Tobacco Company (“NKTC,” joint venture partner);

- NKTC made payments in U.S. dollars to company 1 for the invoice amount, often using a Chinese front company to process the payment;

- Company 1 separately made payments to BATM in the same amount, minus a small percentage commission.

This scheme continued until 2016. Beginning in 2007, NKTC, thought its banks KKBC and FTB regularly used Chinese front companies to process payments between NKTC and company 1 to disguise the North Korean connection to the payments.

OFAC cited “multiple” internal memos and emails showing that BAT managers in Asia knew as early as 2005 that they may be violating sanctions. Even after OFAC designated KKBC and FTB banks, BAT continued to rely on KKBC and FTB as part of the financial network used to disguise the sources and connection to North Korea. OFAC stated that company employees “sought to conceal their apparently violative conduct from banks,” including by letting a wire transfer expire rather than respond to a question from a bank that would have “revealed the payment’s connection to North Korea.”

As an example of BAT’s knowledge of its ongoing illegal activity, on December 29, 2014, BATM’s bank raised questions to company 1’s bank about a pending wire transfer. BATM conferred with company 1 on how to respond to questions about the origins of company 1’s funds sent to BATM and request for documentation. A company 1 employee advised that they should send the bank the sale invoice rather the shipping document because the former “will not show DPRK.” The same company 1 employee noted that “[n]evertheless, we will be caught under question 4,” referring to another question about the origin of funds, and alternatively suggested that they withdraw the wire request and try another bank.

In perhaps the understatement of the year, OFAC noted that this matter “demonstrates that, without a culture of compliance driven by senior management and attendant policies and controls, firms increase the risk that they may engage in apparently violative conduct. Senior management decisions to approve or otherwise support arrangements that obscure dealings with sanctioned countries and parties can be reflected throughout an organization, compounding sanctions risks and increasing the likelihood of committing potential violations.”