Department of Justice’s Antitrust Division Sues Google (Again) for Monopolization of the Digital Advertising Market

In a significant action, DOJ’s Antitrust Division filed a complex complaint against Google charging it with a long-time scheme over 15 years to monopolize the digital advertising market. DOJ was joined by Attorneys General of California, Colorado, Connecticut, New Jersey, New York, Rhode Island, Tennessee, and Virginia.

DOJ filed a separate antitrust case in 2020 against Google for monopolizing search and search advertising, which are different markets from the digital advertising technology markets. The Google search case is scheduled for trial in September 2023.

According to the complaint, Google engaged in a sophisticated strategy to acquire companies to secure market dominance and then engaged in a pattern of exclusionary conduct to expand and entrench its monopoly power.

DOJ filed its case in the Eastern District of Virginia, which has a reputation as the “rocket docket” for processing civil and criminal cases at a rapid pace. DOJ deliberately avoided filing in the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia in an apparent attempt to avoid delays in moving its case.

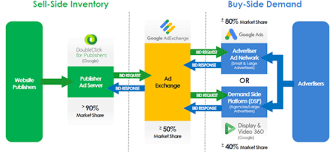

The DOJ complaint alleges that Google monopolizes key digital advertising technologies, referred to as the “ad tech stack” that website publishers depend on to sell ads and that advertisers rely on to buy ads and reach potential customers. Website publishers rely on ad tech tools to generate revenue. Google controls: (i) the digital tool that nearly every major website publisher uses to sell ads on their websites; (ii) the dominant advertiser tool that helps millions of advertsiers buy ad inventory; and the largest advertising exchange (ad exchange) that runs real-time auctions to match buyers and sellers of online advertising.

According to DOJ, Google has long-standing monopolies in digital advertising technologies that content creators use to sell ads and advertisers use to buy ads on the Internet. The effect of Google’s illegal behaviors has been to drive out rival competitors, reduce competition, inflate advertising costs, reduce website publisher revenues and frustrate innovation.

DOJ cited five specific examples of Google’s exclusionary conduct: (1) locking in content creators through tying arrangements; (2) manipulating auctions, including giving itself a “first look” and “last look” advantage over competing ad exchanges; (3) blocking industry participants from using rivals’ technologies and punishing those that attempted to do so; (4) collecting and abusing rivals’ bidding data; and (5) depriving customers of choice by degrading Google’s own services.

Google’s dominance of the digital advertising market allowed it to impose a surcharge on display advertising transactions, a multi-billion dollar market that involves instantaneous auctions each year in the United States. Google estimated that it retains on average 30 cents of each advertising dollar that flows through Google’s ad-tech tools.

Google’s own managers and employees observed its own dominance in the market in a number of examples cited by the Justice Department in which they: (i) characterized Google’s ad exchange as an “authoritarian intermediary;” (ii) stated that switching ad servers for publishers is a “nightmare” that “[t]akes an act of God;” (iii) described the Google scheme to pay publishers “$3 billion yearly” by restricting access to Google Ads and “overcharging its advertisers;” (iv) emphasizing that “[o]ur goal should be all or nothing – use [Google’s ad exchange” or don’t get access to our [advertiser] demand;” (and (v) detailing the company’s steps to “dry out” rivals.”